Every year, drugs are withdrawn from the market because of side effects that are too serious. Almost half of these are found to have a negative impact on heart rhythm. A method to better test this in advance in the lab has come a step closer through research by Birgit Goversen and her colleagues at UMC Utrecht. “In the future, this could also reduce the number of animal tests,” she said.

45% of drugs withdrawn from the market cause severe, and sometimes fatal, cardiac arrhythmias. Animal models are often used during drug development. “But the physiology of each animal – and therefore humans – is different. The results in humans are often different from those from animal experiments. So it would be very nice if we could test drugs on human heart muscle cells but they are hardly available,” says Birgit Goversen, who received her doctorate on July 9 for research on this.

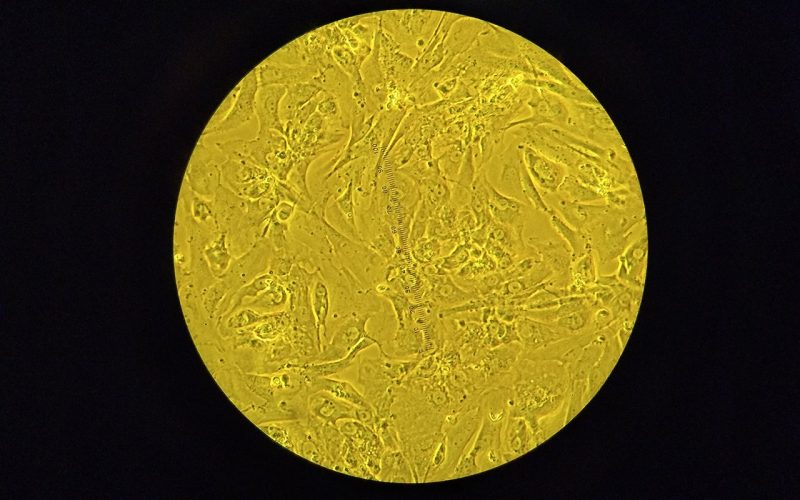

For some time, it has been possible to make stem cells from human skin or blood cells in the laboratory, which then grow back into heart muscle cells. These cultured heart muscle cells are called iPSC-CMs. However, the cultured heart muscle cells in the lab appear to have different electrical properties than those in the human body. Birgit: “The heart muscle cells cause the heart to squeeze and thus pump the blood around, on average about sixty times per minute in healthy adults. The electrical processes inside the cell control each cell to squeeze. However, iPSC-CMs cells in the lab appear to be hyperactive, contracting much more frequently. This makes drug testing on these cells a less reliable result.”

The electrical processes in cells are caused and regulated by different ionic currents of, for example, potassium and sodium. The concentration of these ions inside and outside the cell differs. Through ion channels in the cell membrane, ions can enter and leave the cell, electrical stimuli are generated and distributed throughout the heart by means of a tightly regulated pattern. Thereby, the different types of ions each have their own function. The sodium ions provide activity, the potassium ions provide rest. “Only a good balance will ensure the desired number of heartbeats,” says Birgit. “In the cells in the lab, the potassium ion current appears to be partially missing, which in effect takes the brake off and makes the cell hyperactive.”

In her research, Birgit and colleagues have tried to add this potassium ion current in different ways. For example, by adding genes encoding the ion channel to iPSC-CMs, with success. This reduced the cell’s hyperactivity in the lab. “But with that we don’t appear to be there yet. Each person has unique DNA. So cells derived from different people have different DNA. And that appears to have an effect on the amount of potassium ion channels needed. What produced a good result in one cell line still caused too many contractions in other lines or did nothing at all. So a tailored approach is needed.”

So while this research brings closer the testing of medication in the lab, it’s not there yet. “That’s going to take some time. Worldwide, there are many experiments with iPSC-CMs, which run into similar problems. Moreover, there is a lack of unambiguous guidelines on their use.” This complicates the introduction of a uniform test in the lab that can replace animal experiments. Birgit believes that the test would be acceptable if the behavior in the cell in the lab is sufficiently similar to that of the heart muscle cell in the body. “Because the current situation shows that animal testing also has its limitations.” She is optimistic and has ambitions to develop this method further. “In September I will start as a post-doc at Amsterdam UMC. There we are going to write a business case to see how we can still test acceptably in the lab for suitable drugs for heart patients, so that animal testing will no longer be necessary in the future.”

This research was financially supported by a grant from the “More Knowledge Less Animals” module of ZonMW, the Dutch Heart Foundation and the Stichting Proefdiervrij.

Birgit Goversen