“We’re not there yet, but we’re getting closer and closer.” People with ALS are receiving more and more personalized care, and the first treatments are on the horizon. The ALS Center at UMC Utrecht is a hotbed of innovation. Here, four leading researchers bring together genetic research, clinical studies, laboratory models and care research in the fight against this deadly muscle disease. In this four-part series, read how they aim to make ALS a treatable condition, with the best care for all patients

Genetic research in ALS has an important advantage. It allows researchers to mimic ALS in the laboratory. That’s what Professor Jeroen Pasterkamp is working on. “My research focuses on understanding how ALS arises,” Jeroen says. “What exactly goes wrong in those nerve cells? And what can we do about it?”

prof. Jeroen Pasterkamp UMC UTRECHT

Prof. Jeroen Pasterkamp is professor of Translational Neuroscience at UMC Utrecht and chair of the UMC Utrecht Brain Center. His research connects genetic research with clinical studies with patients.

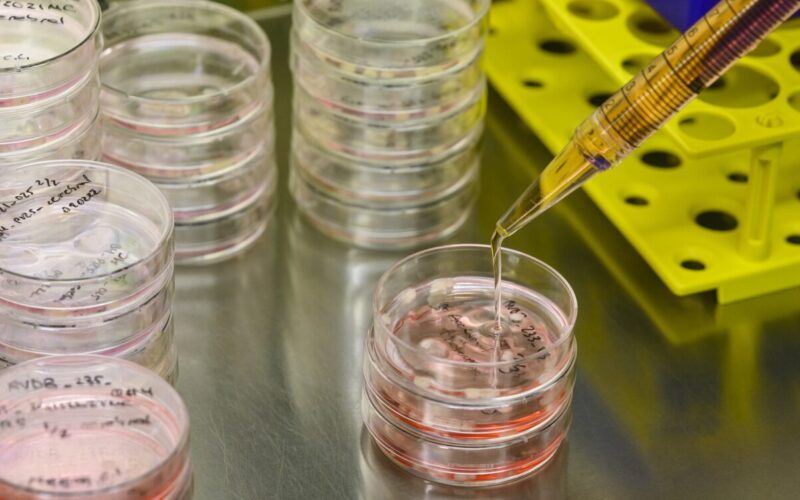

In the laboratory, he grows cells with an ALS gene defect. “This allows us to mimic the disease. This allows us to test new drugs at an early stage. This allows us to develop effective treatments faster.”

Research in the lab with cells from ALS patients

Jeroen talks about the models he uses for his research. “In the past, we often used animal models, such as mice or zebrafish. Now we are moving more and more to human-based models. We almost always ask ALS patients if we can use their cells. This is where we make organoids, or nerve cells made from stem cells.”

A new development is linking nerve cells from the spinal cord to muscle cells on a chip. This allows Jeroen to study the interactions between nerves and muscles, exactly where things go wrong in ALS. “These models allow us to make measurements that are not possible in real patients,” he said.

Not every ALS patient currently has their own laboratory model. Jeroen explains: “We are now focusing mainly on patient groups with hereditary ALS and gene defects that are common. This allows us to set up and fine-tune this system. In the future, I hope this will be possible for every ALS patient. That only makes sense if more treatments become available and we can test them on people with sporadic ALS, who have more different gene defects.”

Future dreams

He continues: “My dream is that in about 10 years, every ALS patient will first have a laboratory model to test different treatments on. Eventually the patient will receive only the best-working therapy. We are not there yet, but we are entering a new phase with ALS research. The Utrecht Science Park is the ideal place for this. This is where the organ-on-a-chip and organoids were largely invented, so I benefit enormously from the immediate area for my research.”