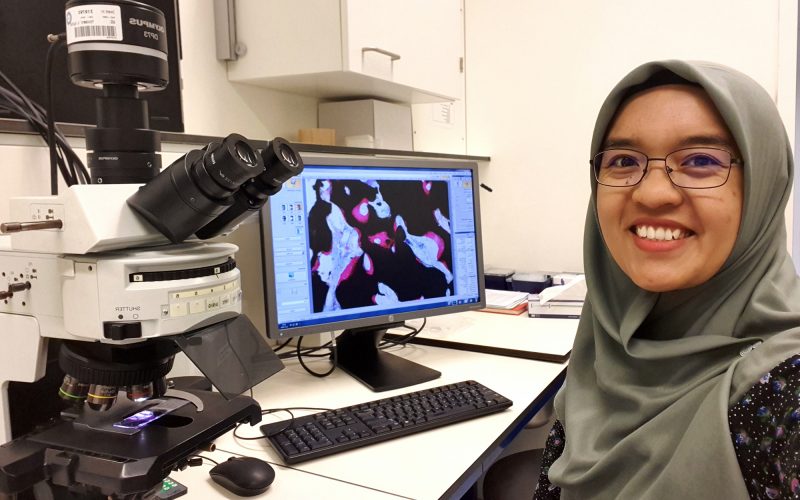

When patients receive a bone implant, doctors usually try to suppress the patient’s immune system to prevent infection. But what if boosting the immune system can actually help heal bones? During her PhD, Nada Rahmani explored this idea. She studied how the immune system interacts with bone implants and looked at trained immunity. Nada found that the immune system is far from passive: “It actively shapes whether implants succeed.”

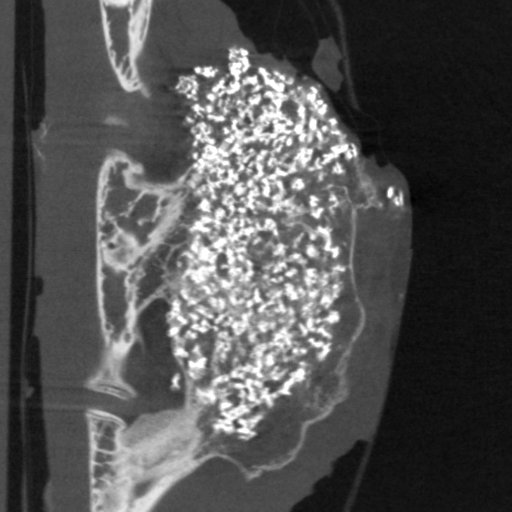

After an injury, doctors often use synthetic implants to repair damage. “These implants don’t just sit in the body”, Nada Rahmani explains. “They interact with immune cells, which can either support or block healing.” Most strategies try to reduce this immune response to avoid infection. While bones often break down during infection, in some patients new bone sometimes grows in unexpected places. “That observation gave us the idea that inflammation might also stimulate bone regeneration”, Nada Rahmani explains. “Together with my supervisors Moyo Kruyt, Harrie Weinans and Debby Gawlitta, we wanted to explore if triggering an immune response can actually help bones heal better.”

For her research, Nada used synthetic implants made from calcium phosphate, a common material in bone repair. “On their own, these implants are quite passive in the body,” she explains. Nada and her team asked: could we make the implants encourage healing by gently stimulating the immune system? To test this, they added small, inactivated fragments of bacteria and fungi. “It’s a bit like vaccines”, Nada says. “You only need small parts of the microbe to trigger a useful response.”

Certain immune stimulants stood out. “Peptidoglycan (part of bacteria) and BCG (vaccine) gave us signals that bone formation was happening”, Nada says. Although most of the tested substances had little effect, these findings showed that the immune system is not a passive player in bone healing.

“The immune system actively shapes whether an implant succeeds.”

“We already know that adaptive immune cells can remember specific diseases”, Nada says. “But we explored a newer idea: innate immune cells, the body’s first responders, can also ‘remember’ past encounters in a broader way.” In her experiments, Nada exposed macrophages to different pathogens and looked at how this affected bone cell formation. “If these cells have fought something before, they respond stronger the next time, even to a completely different pathogen. That’s called trained immunity”, she explains.

Remarkably, this ‘trained’ immune memory changed how stem cells developed into bone cells. “It shows that a patient’s immune history, like past infections, could influence how well their bones heal”, she says. These findings point to ways we could personalize treatments, tailoring care to the patient’s immune system.

One key message Nada takes from her PhD is that the immune system is not a passive player. “It actively shapes whether implants succeed in the long term”, she says. But the field is still a black box. “We don’t yet know if it’s the strength of the inflammation, the type of immune response, or the combination of signals that drives bone regeneration. That’s the big question.”

Doing this work required a highly interdisciplinary team of doctors, biologists, and engineers. “With my medical background, I saw things differently from the engineers and material scientists I worked with”, Nada says. “Those differences often sparked new ideas. But it also meant we had to adapt how we shared our expertise and find ways to connect our work. It made me realize how valuable communication is in any collaboration.”

“It’s not just about the material, it’s also about the person receiving it.”

After her PhD, Nada is reflecting on her next steps, with her interest in the immune system stronger than ever. “Before my PhD, I never thought much about the interaction between immune cells and materials. Now I see there is so much to explore, like how the immune system reacts to microplastics, or how a patient’s own immune status affects implants.”

As a doctor in Indonesia herself, Nada knows every patient is different. “There’s no screening for a patient’s immune status yet, but it can really influence how well an implant works.” That’s why she believes future treatments should not only improve the implant, but also be tailored to the patient. “It’s not just about the material, it’s also about the person receiving it.”

Nada Rahmani, MD (1988, Bandung, Indonesia) defended her PhD thesis on September 22, 2025 at Utrecht University. The title of the thesis was “Microbial Stimulation for Bone Regeneration”. Supervisors were prof. Harrie Weinans, PhD and prof. Moyo Kruijt, MD PhD (both Department of Orthopedics, UMC Utrecht). Co-supervisor was Debby Gawlitta, PhD (Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery & Special Dental Care, UMC Utrecht).