Babies receive essential bacteria from their mothers during birth and immediately afterwards, regardless of whether they are born via natural delivery or cesarean section. Researchers led by UMC Utrecht and the University of Edinburgh report this week in Cell Host & Microbe that mothers are able to transfer bacteria to their babies via multiple transmission routes, which can compensate for each other where necessary. For example, babies born via cesarean section receive less of their mother’s gut microbiome (the bacterial population in the intestines) during birth, but appear to compensate that in part by receiving bacteria from breast milk.

Most research on the microbiome so far has focused on the gut, but the human body also harbors beneficial bacterial communities in other parts of the body, such as in the respiratory tract and on the skin. This study makes more clear how babies, considered sterile before birth, acquire essential bacteria for their various microbiomes after birth. “We wanted to get a better idea of how the microbiome of infants develops in different parts of their body and how it is influenced by factors such as mode of birth, antibiotic use and breastfeeding,” said last author Wouter de Steenhuijsen Piters, physician-researcher and data scientist at UMC Utrecht.

To understand how the microbiome develops in the first month of life, the team examined 120 Dutch mothers and their newborn babies and took repeated samples. From the babies, the team collected samples from the skin, nose, saliva and gut microbiome two hours after birth and then when they were one day, one week, two weeks and one month old. The team also collected six different types of maternal microbiome samples (skin, breast milk, nose, throat, stool and vagina). They then examined to what extent the mother’s different microbiomes determined her baby’s microbiome. In doing so, the researchers were particularly interested in the factors that may influence the transmission of the microbiome, such as mode of delivery, antibiotic use and breastfeeding.

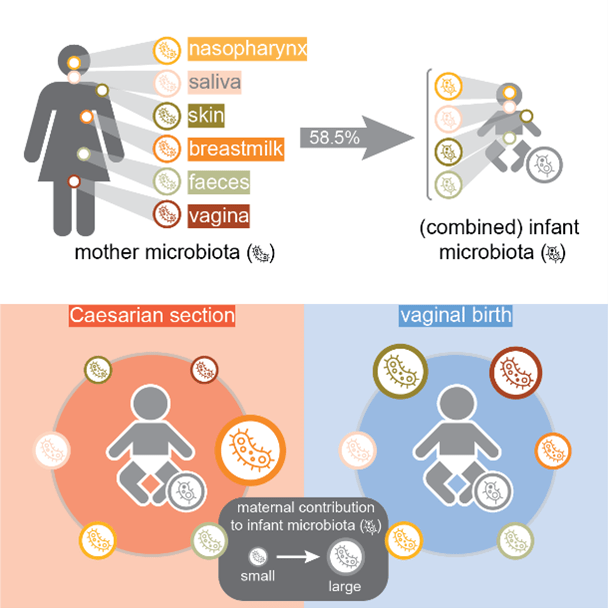

“We saw that mothers can transmit bacteria via various routes, and if some of these routes are blocked for one reason or another – in this case, we saw that happen with the cesarean section – then transmission of microbes to the child can still take place via other routes,” de Steenhuijsen Piters said. Regardless of the birth route, the researchers found that about 58 percent of a baby’s microbiome comes from the mother. However, the transfer of microbial communities from mother to infant was not the same for each route: babies born via cesarean section received fewer microbes from their mother’s vaginal and fecal microbiome, but – apparently to compensate – received more microbes from breast milk. Nevertheless, it cannot be ruled out that children born by cesarean section are still missing essential microbes.

“Microbiome transfer and development are so important that evolution has ensured that those microbes are somehow transferred from mother to child,” said first author Debby Bogaert, professor at the University of Edinburgh. “Breastfeeding becomes even more important for children who are born via cesarean section and who therefore do not get gut and vaginal microbes from their mothers.” De Steenhuijsen Piters adds, “It’s a clever system, and it makes sense from an evolutionary perspective that this kind of microbiome transfer pathway is abundant to ensure that the child can start life with the right ‘starter kit’.”

Graphic abstract

Now the team wants to know more about what other influences might be involved in the development of infants’ microbiome. “We could see that the maternal microbiome explains almost 60 percent of the infant’s total microbiome, but there is still 40 percent that we don’t know about,” de Steenhuijsen Piters continued. “It would be interesting to examine that part as well to see where all the bacteria come from; whether fathers contribute, for example, or siblings, or the environment.”

Ultimately, the researchers want to understand how microbiome development in infants relates to long-term health. “We want to investigate whether early microbiome development influenced by the mother affects not only short-term infection risk in the first year of life, as our previous studies showed, but also longer-term health, particularly with respect to allergies and asthma,” Bogaert says. “In the future, we may be able to use this knowledge to help prevent, diagnose or treat health problems.”

Bogaert D, Beveren GJ van, Koff EM de, Lusarreta Parga P, Balcazar Lopez CE, Koppensteiner L, Clerc M, Hasrat R, Arp K, Chu MLJN, Groot PCM de, Sanders EAM, Houten MA van, Steenhuijsen Piters WAA de. Mother-infant microbiota transmission and infant microbiota development across multiple body sites. Cell Host & Microbe, 2023;31:1-14