Our bodies are covered with large numbers of microbes. The smallest organisms inhabiting your body are collectively known as the ‘microbiome’. The microbiome performs many functions in our bodies and is important for our health. Besides the well-studied gut microbiome, the airway microbiome also plays a crucial role, especially in defending against respiratory infections. Previous studies on the airway microbiome have primarily focused on young children or individuals with respiratory diseases. However, a comprehensive study in a healthy population across all age groups was still lacking. For the first time, researchers from UMC Utrecht, the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), Utrecht University, and the University of Edinburgh (UoE) have investigated this and recently published their findings in the prestigious journal Cell.

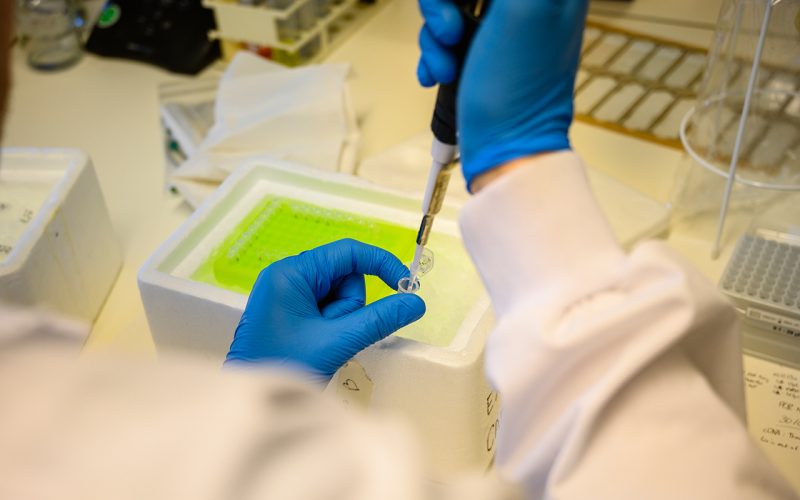

The researchers examined the microbiome of the upper airways from 3,160 healthy Dutch individuals across all age groups, from newborns to those over eighty years old. They collected more than 5,500 samples from the nasal and oral cavities. Using DNA techniques, the microbiome was mapped in detail, analyzing the density, diversity, and composition of the microbiome. The nasal and throat microbiomes exhibited distinct differences. However, the nasal microbiome more closely resembles an individual’s own throat microbiome than that of another person’s throat, suggesting an exchange of microbes between the nose and throat.

Interestingly, the nasal microbiome continues to develop until early adulthood, in contrast to the throat microbiome, which—like the gut microbiome—is fully developed during childhood. The development of the nasal microbiome differs between men and women, with these differences emerging during puberty, possibly due to hormonal changes. In addition to age and sex, season also affects the composition of the nasal microbiome. Conversely, the throat microbiome is primarily influenced by lifestyle factors such as smoking and diet, with antibiotics significantly impacting its microbial composition.

Finally, the researchers were able to show that the airway microbiome differs in people who have recently experienced mild symptoms of a respiratory infection. Although these symptoms were likely caused by respiratory viruses, they clearly affected the composition of the microbiome. In the nasal microbiome, more pronounced differences were associated with more severe respiratory symptoms accompanied by fever. A history of pneumonia in the past three years was also linked to changes in the nasal microbiome. These findings demonstrate a clear relationship between the microbes present in our airways and respiratory health.

The study is the most complete atlas of the upper airway microbiome in healthy individuals to date. The results provide an important basis for further studies on the role of ‘healthy’ microbes in susceptibility to infections and their severity throughout life, as well as the factors influencing this process. This remarkable publication is the result of both national and international collaboration and forms a crucial basis for advancing our understanding of the microbiome in relation to respiratory health and disease.

Odendaal M-L, Steenhuijsen Piters WAA de, Franz E, Chu MLJN, Groot JA, Logchem EM van, Hasrat R, Kuiling S, Pijnacker R, Mariman R, Trzcinski K, Klis FRM van der, Sanders EAM, Smit LAM, Bogaert D, Bosch T. Host and environmental factors shape upper airway microbiota and respiratory health across the human lifespan, Cell 2024;187:1-15 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2024.07.008