On this page, you’ll find detailed information about a range of powerful imaging methods that allow scientists to visualize cellular structures and molecular processes with unprecedented clarity and precision.

We value your interest in our research facilities and technologies. Whether you’re a fellow researcher, potential collaborator, student, or member of the public, we’re here to assist you.

When ultrastructural morphologic analysis is required, conventional EM is the technique of choice. After aldehyde fixation and post-fixation with osmiumtetraoxide the biopsies, tissues or cultured cells are embedded in epoxy resin. This allows ultrathin sectioning of 50-70 nm sections. After additional staining with uranium and lead salts the ultrastructural morphology can be investigated in the electron

microscope.

The most widely used approach to detect proteins in cells is immuno-electron microscopy. Many protein-sorting events that determine live or death in a cell occur in 40-60 nm, often coated, membrane subdomains, which are below the detection level of the light microscope. The Tokuyasu cryosectioning technique has been improved and perfected in the Cell Microscopy Center so that it now generally surpasses other techniques in membrane visibility and labeling sensitivity. The method includes that cells are chemically fixed, after which they are frozen and cut into 50-100 nm cryosections. The sections are thawed and labeled with antibodies that specifically recognize the molecule of interest, followed by gold particles that are detectable in the EM.

Ultrathin sections (50-70 nm) provide an excellent way to observe the interior of a cell. However the thickness of a section diminishes the chance that 3D relations between organelles are found. Using thicker sections (200-300 nm) this chance is increased. When such a section is rotated from +65 to -65 º in an a 200KV electron microscope and a picture is taken every degree, the 3D ultrastructure of an area of interest can be visualized using special software.

After embedding in resin, images of the sample surface can be made using a scanning electron microscope. If 3D information is required the Fib-SEM can mil a way the surface using a focussed ion beam.

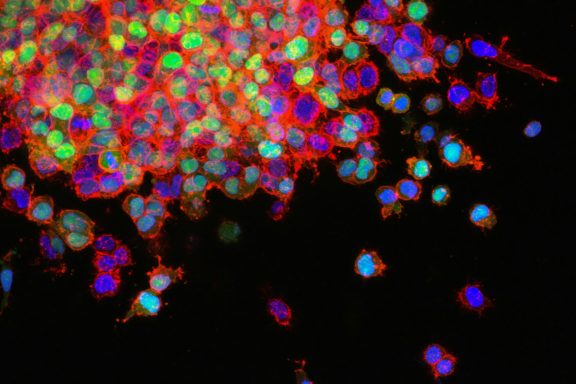

The use of green fluorescent protein (GFP) to study dynamic processes in living cells has led to a revival of fluorescence microscopy. Because GFP and its variants are genetically encoded and emit visible fluorescence without the need for cofactors, they can be tagged to almost any protein to reveal in living cells its real-time kinetics and directionality of intracellular transport. Live-cell imaging provides an exceptionally powerful method to study dynamic intracellular systems.

Live-cell CLEM (Correlative Light- and Electron Microscopy) imaging reveals the dynamics of protein and organelle movements, yet lacks the structural resolution against which the fluorescent signal can be interpreted. Immuno-electron microscopy is unique in its capacity to localize molecules to their functional intracellular locations, but is limited in its interpretation of dynamic processes. To fill this gap between live-cell imaging and EM we have recently developed a correlative-microscopy method by which a fluorescent protein followed by live-cell imaging at any time during its itinerary can be processed for visualizationby immuno-EM: by incubating cryosections with antibodies against e.g. GFP, we gold-label the previously fluorescent molecule. The advantages of this correlativetechnique are numerous. For example, by using antibodies conjugated to differentgold sizes (e.g. 5, 10 and 15 nm), we can co-localize the formerly fluorescent proteinwith relevant marker-, machinery- or cargo-molecules, yielding crucial information on the structural-molecular environment of the protein.

Reference: 10.1016/bs.mcb.2022.12.022

In the electron microscope rare cellular events or abarrant cells in a tissue are hard to find. In the light microscope the field of view is much larger which allows rapid identification of the region of intrest (ROI). When an ultrathin section is processed for immuno-electron microscopy (on a special grid with location markers) it is possible to view the section on the grid in a sensitive light microscope and locate the ROI.

Next the grid can be investigated in the electron microscope for context information.

The cell of interest is located quick using the grids location markers.

Reference: doi: 10.1083/jcb.202106044

For some applications HPF instead of chemical fixation is preferred. Fresh samples are first frozen and then special ways of chemical fixation are applied. The freezing is done under high pressure so that ice crystal formation is prevented.These vitreous frozen samples can then be chemically fixed in three ways: